6 Ways to Scaffold Complex Texts

Interested in a FREE planning template to support your instruction? Scroll down to the end of this blog post for the link!

With instructional level theory now being widely refuted, significant shifts have occurred in how teachers approach reading instruction within classrooms across the world.

The long-held and pervasive belief that if we give students texts that are too challenging, frustration levels will rise and learning won’t occur, was entrenched in teaching practice for far too long. Emmett Betts, author of Foundations in Reading Instruction, coined the term ‘instructional level’, arguing that learning was facilitated by finding students’ reading levels and proposing that “maximum development may be expected when the reader is challenged but not frustrated” (Betts, 1946, p.448). According to Betts, ‘frustration level texts’ were those “…presumed to be too challenging from which to learn from.”

He claimed that if you matched kids to text using the criteria he proposed (95-98% word reading accuracy and 75-89% reading comprehension), kids learned more (Shanahan, 2017).

Like many other teachers, I too mistakenly believed that the best way to help students grow as readers was to teach reading using ‘just right texts’. In other words, material that could mostly be comprehended on their own and that wouldn’t be so demanding they’d want to give up.

But here’s the catch: this approach isn’t supported by research.

Unfortunately, teachers were led to believe it was.

The whole idea of assigning a precise ‘reading level’ is shaky at best. It is nearly impossible to accurately determine the exact level of a student or a text.

“The instructional level continues to be a confusing construct that is often conflated with a measurement system that has been consistently refuted by research.” (Burns, 2024, p.8.)

While I can somewhat appreciate the notion that if a reading task is too challenging for a student, there is greater potential for disengagement and demotivation; the idea that we simply remove the challenge altogether and replace it with something easier is a harmful approach if we truly want students to make progress in reading and access grade-level curriculum.

In fact, research indicates that productive struggle can increase motivation, despite the common argument otherwise (Killeen, 1994). Furthermore, studies have shown that students working with more challenging texts (even up to four grade levels above their predetermined ‘instructional level’) perform better than those working only with instructional level texts, and that working at only an ‘instructional level’ either offered no benefit or hindered student learning (Morgan, Wilcox, & Eldredge, 2000; Homan, Hines, & Kromrey, 1993; Kuhn et al. 2006).

The fact is, if a student is continuously being given texts that are below grade-level standards to try and ‘match’ them to reading material that is accessible ‘mostly’ independently, we are severely hindering that child’s learning and potential to catch up. Students who have achieved a sound level of decoding skills should be engaging with challenging texts and being explicitly taught how to read them.

As Shanahan (2019, p.22) points out:

“Restricting students to easier materials usually means preventing them from dealing with content at their age- or maturity-levels and may serve to isolate these children from their social peers.”

To be clear: I am not suggesting that we hand students a complex text and expect them to figure it out on their own. The point isn’t to overwhelm learners with material that feels out of reach, but rather to ensure they have access to grade-level texts with the right scaffolds in place. Avoiding these texts altogether creates an equity issue. If some students are consistently shielded from challenging material, they’re being denied opportunities to grow.

This is where our role as teachers becomes critical. Our task is not to remove the challenge, but to become skilled at identifying the potential barriers a text might present and provide scaffolds that help students overcome them.

After all, “…reading is the ability to make sense of a text, and that means being able to negotiate any barriers to understanding that the texts may include.” (Shanahan, 2017, p.19)

My goal as an educator has always been to uncover the ‘how’.

While I love exploring the research and theoretical understandings underpinning the ‘why’ of effective instruction, there is always the same question circling my mind: “Yes, but…How?”

I want to know what the theory looks like in practice, and how we can accomplish these ambitious goals within the classroom. How do we take these big ideas and turn them into concrete practices that actually move our learners forward?

Which brings me to the focus of this post: How do we scaffold challenging texts in such a way that helps our students grow as readers? This is the question that I have been diving into recently, and it’s the inspiration behind today’s blog. I was first prompted to explore this topic after listening to Timothy Shanahan’s recent podcast. His discussion was packed with helpful ideas, many of which teachers can immediately put into practice.

In the following section, I will share 6 practical strategies teachers can use to support students as they engage with complex, demanding texts.

Before we dive in, it’s worth taking a moment to consider the following points identified by Timothy Shanahan:

The scaffolds provided by the teacher will depend on the specific text and whether those features are disrupting a student’s comprehension.

“The harder a text is for a student, the more there is to learn, which is a positive thing.” (2017, p.20)

“The harder a text is relative to the current reading abilities of the student reading it, the greater the instructional support needed for success” (2017, p.20).

Make sure that children have solid foundational skills in decoding before increasing the complexity of the texts used to teach reading. Several studies have shown that second grade is not too early for students to deal with more complex texts successfully.

Developing proficiency with and deriving knowledge from each text a student works with is the ultimate goal. The scaffolds and supports we choose to implement with each text should work to achieve this goal.

1: Pre-teach Vocabulary

It probably comes as no surprise that teaching key vocabulary prior to reading a complex text is an important and effective scaffold. It is estimated that more than 80% of students’ reading comprehension test scores can be accounted for by vocabulary knowledge (Rasinski, 2017), so dedicating time to vocabulary building and instruction is a worthwhile endeavour.

The tricky part, of course, is deciding which words to focus on. We can’t possibly teach every difficult word within a text, so we need to be strategic!

Here are a few guidelines to help you choose the most impactful words to teach ahead of time:

Choose words that the author does not explicitly explain or define. To begin with, skip over words students can figure out using context.

Focus on vocabulary that cannot be easily decoded.

Look for morphological connections. If several tricky words share common roots or affixes, draw attention to those links so students can apply that knowledge to other words. The majority of commonly used academic words – up to 76%! – are connected by morphemic patterns. When we move into content-specific areas of study, that percentage increases (Eide, D. 2011).

Prioritize Tier 2 academic vocabulary. For example, words like contrast, identify, or analyze transfer across subjects and are essential for building academic language.

Provide opportunities for students to use targeted vocabulary in writing, speaking, listening. Frequently reviewing and using new words plays a significant role in building students’ lexicon.

Practical ways to pre-teach vocabulary include:

Giving students a glossary. Consider including visuals as an additional scaffold, which can be especially helpful for bilingual and multilingual learners. Interested in a free glossary template? Click here!

Using organizers, such as a Frayer Model, to break down complex vocabulary (best used for high-leverage words that students are likely to encounter frequently within academic content)

Implementing morphology routines to build morphological awareness and students’ ability to tackle multisyllabic words (check out this blog post if you’re interested in reading more on this).

Building a word wall that includes the word, a student friendly definition, a visual, and examples of the word used in context. Keep it interactive by revisiting the wall whenever students encounter those words in the text.

2: Build Background Knowledge

Background knowledge is one of the most powerful factors in reading comprehension. In fact, “Research shows that background knowledge is a strong predictor of comprehension of a text on that topic, even more so than reading proficiency.” (Cunningham, Burkins, & Yates, 2021, p.27)

To comprehend a complex text, readers often need to make inferences beyond what is explicitly stated by the author. This requires combining prior knowledge with new information in the text. When students lack sufficient background knowledge about the subject matter they are reading about, their ability to make accurate inferences is impacted. They struggle to connect the dots, and meaning breaks down.

When planning for knowledge-building as a scaffold, consider asking (Shanahan, 2019):

Within this specific text, what knowledge does the author assume the reader already has?

Are students likely to have this knowledge?

Can students reasonably bridge that gap on their own?

What information will support interpretation of the text – without telling information that the text provides?

Ways to build background knowledge before reading include:

Showing students visuals, such as photographs, videos, diagrams, maps or artefacts.

Explicitly teaching key vocabulary.

Using connected texts to ‘fill gaps’ about a topic.

Keep in mind: the goal is to give students just enough knowledge to access the text, without overwhelming them or replacing the reading experience itself.

3: Focus on Fluency First

When tackling a complex text, many teachers naturally begin with comprehension strategies and close reading. However, Shanahan (2019) suggests that placing fluency at the forefront of reading a complex text might make sense for some students.

Flipping this process so that fluency is the starting point can give students a chance to hear and practice the text aloud before analyzing it, setting them up for much deeper understanding.

One powerful strategy is Dyad Reading, whereby the teacher models appropriate phrasing, expression and pronunciation while the student reads along in sync. Students benefit from multisensory input – seeing, hearing and saying the words together – while also internalizing what fluent reading sounds like.

Other effective fluency-first routines include:

Echo reading: The teacher reads a phrase or sentence, and the students echo it back.

Choral Reading: The whole class reads aloud together, reducing pressure on individual students.

Repeated readings: Students reread a short passage multiple times to build automaticity.

Research shows that pre-reading fluency work can significantly improve comprehension (Brown, Mohr, Wilcox, & Barrett, 2017). The goal isn’t just speed—it’s expression, rhythm, and accuracy, all of which signal deeper understanding of the text.

4: Identify and Study Complex Sentences

One way that texts become increasingly complex is through the varied ways authors express ideas at a sentence level. As Joan Sedita (2020) notes, “The ability to understand at the sentence level is in many ways the foundation for being able to comprehend a text.”

When planning to scaffold a challenging text, identify sentences that may present a barrier to comprehension due to their complexity. Shanahan (2025) suggests asking students questions about the content of these sentences to gauge understanding. If students cannot answer the questions, guide them through the process of examining and breaking down those sentences into meaningful parts to support comprehension.

Additional strategies might include:

Chunking: breaking sentences into smaller phrases and paraphrasing each part

Sentence combining or deconstruction: helping students see how clauses and phrases fit together

Highlighting connectors: pointing out conjunctions or transitions that signal relationships between ideas

These routines not only help students access difficult texts, but also build a foundation for producing more sophisticated writing themselves.

5: Build Awareness of Cohesion

Cohesion refers to an author’s use of pronouns, synonyms and other connecting words across a text.

In my experience, cohesion can often become a somewhat ‘hidden’ barrier to students’ comprehension. As texts become more complex, keeping track of who ‘they’ are or what ‘it’ refers to can become increasingly difficult, especially for struggling readers.

By guiding students to refer back to the text and identify who ‘they’ is referring to, or who ‘she’ is, we can build their awareness of how authors use cohesion to create flow. Additional scaffolding might include having students highlight, underline, or color-code a text to show where repetitions, synonyms, pronouns, or transition words occur.

Joan Sedita outlines a variety of instructional strategies that teachers can use to build students’ confidence in this area. You can read about those in her blog post linked here.

6: Target Text Structure

A powerful way we can help our students tackle complex texts is by teaching them to recognize how the text is organized. There are five commonly used structures (also called ‘patterns of organization’) that authors use to organize their ideas: description, sequence/chronology, compare and contrast, problem and solution, and cause and effect.

Interventions aimed at developing students’ understanding of text structure - and how to use it during reading - have shown positive results in upper elementary and middle-school (Wijekumar, Mayer, & Lei, 2017).

When a reader is able to recognize the structure of a text, it “enables the reader to strategically build mental representations similar in organization to the author’s organization” (Wijekumar, Mayer, & Lei, 2017, p.3), and to identify “the most important elements of the text through the main idea patterns for each text structure.”

Consider scaffolding text structure instruction by:

Explicitly teaching or reviewing the structure of the text prior to reading

Highlighting transitional words and phrases (e.g. however, as a result, in contrast, first/next/then) so students can see how ideas are linked.

Providing a relevant organizer to guide students’ note-taking and idea recording (e.g. a Venn Diagram, flow chart or t-chart).

Final Thoughts and a Freebie

I’d like to leave you with one final piece of advice from Timothy Shanahan on this topic:

“Let the kids in on the secret.”

This resonates with me as I’m a firm believer in communicating with students the what, why, and how surrounding learning.

Being transparent matters, and it makes a difference.

When kids know upfront that they’ll be tackling challenging texts, and can see that the teacher believes they are capable, it can help them to approach the task with more confidence. Instead of feeling like the work is ‘too hard’, we have the power to help our students reframe the challenge as an opportunity to grow.

And here’s the best part: the pride students feel after successfully wrestling with a difficult text is contagious. Once they’ve experienced that sense of accomplishment, they’ll be more motivated to dive into the next challenge.

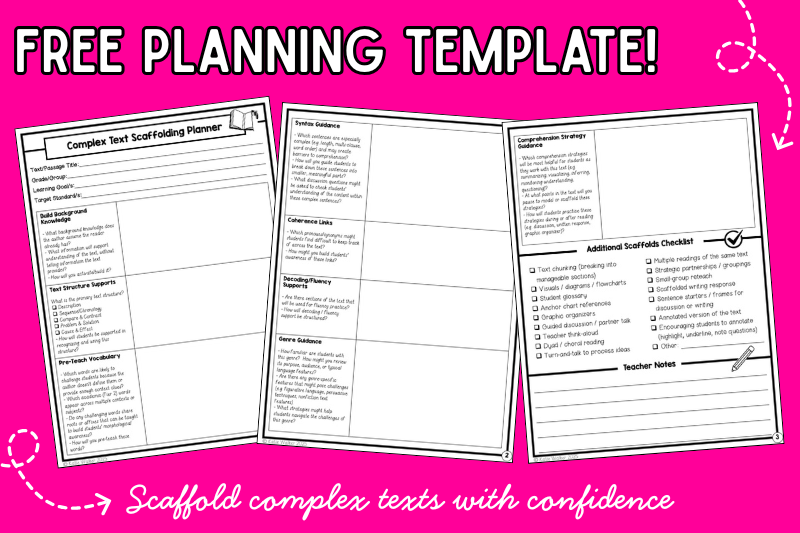

To help you put these ideas into practice, I’ve created a free planner you can use to design your own scaffolding plan for complex texts. This planner can be used with any complex text to help you identify the most effective scaffolds for your students.

Click here for this free download!